It’s the spring of 1925 and the air in Hanover, New Hampshire is buzzing with the promise of new beginnings. Teddy had just graduated from Dartmouth College and was about to try to realize his dream of becoming a writer. Not just any writer, but one who could make the world giggle in delight. Little did he know, the road to literary success would not be in a straight line but with many twists and turns.

Teddy had always been a dreamer. At Dartmouth, he’d edited the humor magazine, The Jack-O-Lantern, filling its pages with witty quips and bizarre sketches of creatures that didn’t exist but should. His professors had raised eyebrows at his tendency to turn essays into rhyming rants about imaginary beasts, but his classmates adored his oddball charm. Now, diploma in hand, Teddy packed his bags and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, his hometown, determined to make his mark as a writer. He envisioned himself penning stories that would leap off the page, stories that would dance in the minds of readers like a parade of polka-dotted elephants.

His first attempt was to write for the local newspaper, The Springfield Union. The editor, a gruff man named Mr. Snickersnee, squinted at Teddy over his glasses. “We need hard-hitting stories” he barked. “Bank robberies, city council scandals, factory strikes. Can you handle that?”

Teddy nodded eagerly, his mind already spinning with possibilities. “Oh, I’ll write stories that’ll make your readers’ hats fly off!” he declared, though Snickersnee’s skeptical frown suggested he wasn’t entirely convinced.

Teddy’s first assignment was to cover a bank robbery that had shaken Springfield’s quiet streets. Three masked men had stormed the First National Bank, making off with a sack of cash and leaving the tellers in a tizzy. Teddy sat at his typewriter, his fingers itching to craft something extraordinary. But instead of a straightforward report, his words took a peculiar turn:

In the town of Spring-a-ling, where the bank bells always ring,

Came three sneaky Zizzle-Zats with their sacks of knick-knack flats.

They twirled their mustachios, oh so grand and villainous,

And snatched the gold with a hop, skip, and a bilious!

He paired the story with a sketch: three bandits with elongated noses and striped top hats, riding a contraption that looked like a bicycle crossed with a pogo stick, their loot spilling out in a cascade of glittering coins. The drawing was unmistakably Teddy’s—whimsical, exaggerated, with lines that curved like a rollercoaster and colors that popped like firecrackers.

When he submitted the piece to Snickersnee, the editor’s face turned the color of a ripe tomato. “What in blazes is this?” he roared, waving the paper. “Zizzle-Zats? Bilious? This isn’t a fairy tale! It’s a bank robbery! Give me facts, not this… this nonsense!”

Teddy, undeterred, tried again. This time, it was a story about a city council meeting where a heated debate over a new park had erupted. Teddy’s imagination, however, refused to stay grounded:

In the Hall of Yip-Yap, where the councilors clap,

Sat Mayor McSnoot with his tie in a loop.

They argued and bickered, their voices all flickered,

Till a park plan was born with a Whirly-Whoo-Scoop!

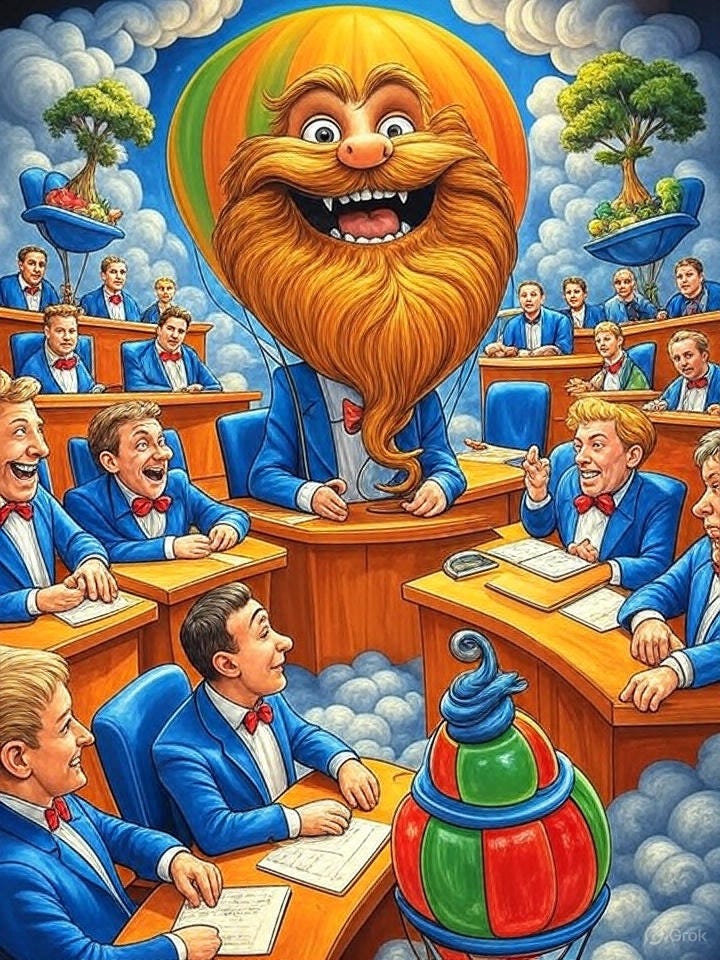

Accompanying the article was another drawing: a council chamber filled with men in bow ties that sprouted wings, their desks floating above a sea of green jellybeans. The mayor, McSnoot, had a beard that curled like a spiral staircase, and the Whirly-Whoo-Scoop was a machine that looked like it could plant trees and serve ice cream simultaneously.

Snickersnee nearly choked on his coffee. “This is a newspaper, not a circus!” he bellowed. “You’re fired unless you can write something normal!”

Teddy’s heart sank, but his spirit remained strong. He loved his rhymes, his creatures, his wild, wobbly world. He couldn’t help it—the world refused to stay mundane in his hands. He tried one last time, covering a factory strike where workers demanded better wages. Surely, he thought, he could make this work. But once again, his pen danced to its own tune:

The Widget-Whack workers, those brave little larkers,

Marched round the factory with signs held up high.

With a chant and a cheer, they made bosses all fear,

For their Whackety-Woo would not waver or die!

His sketch showed workers with colorful hardhats, wielding signs shaped like giant machine gears, marching in a conga line around a factory that spewed rainbow smoke. The scene was chaotic, joyous, and utterly absurd.

Snickersnee didn’t even finish reading before tossing the pages into the trash. “Ted,” he said, his voice weary, “you’ve got talent, but it’s not for news. Go write for lunatics. You’re done here.”

Teddy left the newspaper office; his portfolio of rejected stories and drawings tucked under his arm. He felt the sting of failure, but also a spark of defiance. If the world didn’t want his Zizzle-Zats or Whirly-Whoo-Scoops in its newspapers, he’d find another way. He began submitting his work to magazines, hoping to find a home for his peculiar tales. But editors at The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s sent back polite rejections, calling his work “too fanciful” or “not suitable for our readers.” One editor suggested he try illustrating advertisements instead.

So, Teddy did. He landed a job drawing ads for Flit, a bug spray company, where his quirky creatures found a temporary home. His drawings of giant mosquitoes and comical insects were a hit, but his heart still yearned to write stories. He spent his evenings at his desk, crafting tales of places and creatures, each page adorned with drawings that seemed to wiggle and wink at the reader. Yet, publishers remained skeptical. “Too strange,” they said. “Too silly.”

One night, as Teddy sat in his small Springfield apartment, surrounded by piles of rejected manuscripts, he stared at a sketch of a creature with a tufted head and a mischievous grin. It was a Zizzle-Zat, one of his bank robbers, now repurposed into something new—a character in a world where rules were made to be bent. He realized then that his failure at writing “normal” stories wasn’t a failure at all. It was a sign. The world didn’t need another reporter churning out dry accounts of bank robberies or strikes. It needed him.

He began to focus on children’s stories, pouring his heart into tales that celebrated the absurd and the impossible. His first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, was born from the ashes of his newspaper days, inspired by the rhythm of a ship’s engine on a voyage home from Europe. It was rejected by 27 publishers before Vanguard Press took a chance on it in 1937. The book, with its parade of fantastical sights and oddball flair, marked the birth of Dr. Seuss—a name Theodore Geisel had used as a pen name since his Dartmouth days, when he’d signed his Jack-O-Lantern pieces to dodge trouble with the dean.

Great one! He’s one of my favorites.